How Does Impeachment Work?

October 3, 2019

Currently, the United States House of Representatives is in the midst of a fiery impeachment inquiry of our current president, Donald Trump. Though impeachment is a rare and interesting occurrence, many people don’t exactly know what it is, how it works or what it means.

Though impeachment is supposed to be a set procedure, the way it has been run and operated over the past 100 or so years has varied greatly. The first president to have been confronted with impeachment article was Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States. The House of Representatives voted to impeach him, but the Senate voted to acquit him by a margin of one vote. In the second case of impeachment, Bill Clinton was impeached by the House of Representatives, but was subsequently acquitted by the Senate by a margin of 22 votes.

Essentially, the preparation for impeachment process begins in the House of Representatives. The House of Representatives can open an investigation into the President’s supposed-misdoings at any time, which has just occurred. They can investigate for a theoretically unlimited amount of time without a vote, but once the Representatives think they have a decent case against the president, they must vote on the impeachment itself.

This investigation isn’t even the start of impeachment proceedings as stated in the constitution, but simply preparation for the case.

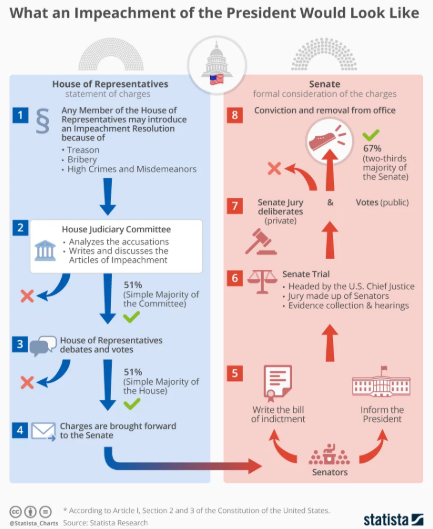

First, a Representative must simply introduce the impeachment articles or proceeding to an assembly of the House of Representatives. Then, this proposal moves to the Judiciary Committee for a vote on whether to introduce the proceedings to the central assembly House of Representatives for a vote. If the Judiciary Committee votes more than 50% in favor of the resolution, then the proposal gets introduced to the general House of Representatives for further consideration. Then, the House of Reps must vote in another simple majority (a majority higher than 50%). If all of this occurs successfully, the House has officially and successfully impeached the president, but the process is far from over.

As aforementioned, the other presidents who were ̈impeached ̈ended up being acquitted completely of their supposed crimes by the Senate. Now that the House of Representatives has voted to impeach the president, the Senate must approve of the impeachment. Essentially what occurs is a trial-like assembly of the Senate in which members of the House of Representatives act as prosecutors (in an attempt to persuade the Senate that the president is guilty) while the chief justice of the Supreme Court acts as a judge or moderator of the proceedings. The president can also send a counsel to defend him, but he cannot be there himself, as the framers believed that he had to be able to fulfill the responsibilities of the presidency without distraction.

This is where the impeachment process gets a little fuzzy. Over the course of two unsuccessful impeachments and 100 years, the process of this Senate trial has morphed. Depending on who you talk to, there are a lot of different ways to conduct this meeting of the Senate. It seems that whatever the current Senate body wants to do is allowed, as long as it follows the basic guidelines set forth by the framers of the Constitution.

Finally, to fully impeach the president, the Senate must vote in a 2/3rds majority to find the President guilty and remove him from office. If this does not happen, the country returns to business as usual.

The impeachment process was created by the framers of the Constitution as a sort of fail-safe, in case every single safety net fails and falls apart. It was intended to be long and hard to execute, as to make sure the governing bodies definitely knew what they were doing.