A Student Perspective on Historical Perspective: Approving Black/African American and Latino/Puerto Rican Studies

The Connecticut State Education Resource Center has designed a Black and Latino studies curriculum to fulfill the new state requirement. The Fairfield Board of Education is in the process of vetting the curriculum and implementation for FPS students in the 2022-2023 school year.

The Fairfield Board of Education will be voting on Tuesday, December 14, whether to grant approval to the proposed Black/African American and Puerto Rican/Latino studies course, as a high school, full-year history credit at Warde and Ludlowe. The discussion surrounding this course was predicated by CT Public Act 19-12, which mandated that all high schools in Connecticut offer a course in African American and Latino studies beginning with the 2022-2023 school year—the first in the country to do so. Following the passage of the Act in June 2019, the Connecticut State Education Resource Center (SERC) has worked to develop robust curriculum, professional development, and other open-access resources. Each high school has the discretion to cater the course format to best fit their needs, including offering it as a core US history credit, an elective, or even an interdisciplinary course alongside language arts or world language. A committee of teachers, administrators, students and other stakeholders has discussed implementation at Ludlowe since the curriculum was fully released in July 2021, and presented to the Board of Education on October 12 and November 30.

Throughout the process, the advisory committee has continuously refined the vision of the course in response to Board of Education concerns about enrollment, rigor, and core US history objectives. Initially, Lisa Olivere, the FPS Director of Social Studies and Student Centered Learning, and her colleagues presented the course as a two-credit English and history experience; however, due to concerns that the literature list was unformed, the course is now proposed as a one-credit history experience. The committee has confirmed that students taking the course can receive three college credits from Sacred Heart University upon successful completion, similar to other Early College Experience (ECE) courses in place at Ludlowe. Despite the college credits tied to the course, it is intended to be open to all students; the only prerequisites are Global Studies 9 and Modern Global Studies 10 which students will have taken before junior year. Many hope that this will narrow the achievement gap at FPS by offering another college credit opportunity that is not tied to the rigid and prescribed Advance Placement program.

Currently, the committee is advocating for the course to fulfill the US history credit rather than simply an elective credit. If the Board of Education approves this motion, juniors will have the opportunity to select a traditional US history course (college prep, honors, or AP), an interdisciplinary experience (AP American Studies), or this proposed ECE African American and Latino Studies course. Since the Connecticut State Department of Education has mandated this course offering, students can expect to see it in the Program of Studies this spring. However, the US history credit for the course (which, should be mentioned, is a graduation requirement unique to Fairfield) is on the line. The course would also be open to select seniors who did not have the choice to take the course last year.

The Board of Education discussions surrounding the course have cut right to the heart of who defines American history. BOE member Jennifer Maxon-Kennelly has stated, “I think this course is long overdue…but I do not support one perspective fulfilling a survey US history requirement.” Chair Christine Vitale argued, “I do view [the course] as a US History class…We teach history so our students know where they came from.”

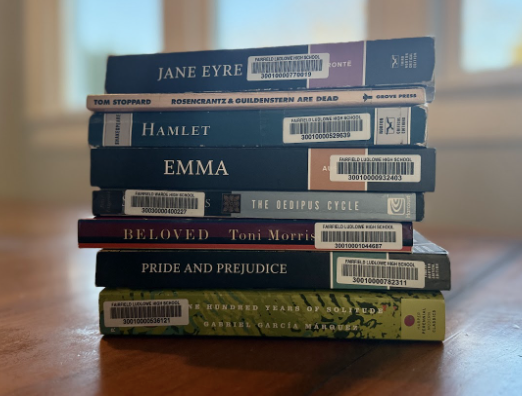

The history of African American and Latino peoples, who have contributed immensely to American institutions, labor, arts and culture, and identity, often while experiencing outright oppression or discriminative treatment, is American history. Just as each person brings their own associations and life experience to the table, a course narrated from the perspective of African American and Latino peoples will view US history from a different lens than the one to which many of us have been accustomed. Many students, including Maddie Depiano and Andrew McKinnis from Ludlowe, have commented at Board of Education proceedings that the traditional US history course does not adequately address the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and people of color. This conversation has unearthed a broader need to update the entire US history curriculum so it reflects diverse perspectives; however, the approval of the African American and Latino course should not wait until the standardized course is made more encompassing.

Additionally, decentering American history from the perspective of white peoples does not mean telling it from only a single perspective. Students will engage with African American history for the first semester and Latino history for the second semester; within each of these cultures is not a homogeneous but a varied experience of enslavement and freedom, politics and protest, ancient origins and modern-day immigration. BOE member Jennifer Maxon-Kennelly raised concern at the BOE Town Hall on December 8 that the curriculum would provide a “type of college specialization in a course that is required for all students” rather than a broad overview of US history. However, Superintendent Mike Cummings has provided context that “telling the American story in 182 days is always going to prevent complete coverage.” The time limitations placed on high school history teachers, as well as the present curriculum’s need for revision, necessitate that any one class cannot view American history from all angles and cover all events that have shaped our nation into what it is today. There is concern that students enrolling in the new course will not be exposed to the indigenous perspective, the Anglo-American perspective, or the Asian-American perspective, but arguably the Latino perspective has been left out of our current curriculum aside from a few references to twentieth-century agricultural labor and immigration. The course does not purport to be an encompassing narrative—its title frames its specific lens and limitations—and will continue to provide students with primary sources and difficult questions that teach them to be critical thinkers, like any other history credit.

Since the ambition to cover all historical perspectives and events in one course is unattainable, I think it is useful to view the entire conversation from a different lens: essential questions and historical themes. Questions of what defines American citizenship, how we have interacted with our environment and natural resources, and who should be included in “We the People” cut across multiple courses. Lauren Marchello, Jeremy Timperanza, and Anna Newberg, history teachers at Ludlowe, have prepared a curriculum crosswalk outlining the more than 150 historical events and overlapping questions that the AP US History course and the proposed credit present in common. As Kevin Staton, a librarian at Fairfield Warde High School and the Co-Chair of the FEA Anti-Racism Committee, shared at a recent BOE Town Hall, “[African American and Latino studies] is just an example of one group that is intersectionally woven into American society.” Students taking the new credit offering will still learn about the Declaration of Independence, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the US Constitution, the Missouri Compromise, and Manifest Destiny; more importantly, they will engage with and synthesize the themes of US history.

History provides value by allowing us to understand the decisions made, some inconsequential and some monumental in the past, and shed insight on future progress. But for African American and Latino students who have not seen themselves fully represented in the curriculum before, history also allows them to better understand their identity. It is important to note that as a white student, I can debate this course on its merits, but for other students, it may feel as though the weight of their entire 400 year history is being placed on the line. Laila Henry, a student at Fairfield Woods Middle School who describes herself as mixed race, spoke during public comment on November 30, “When Board members said that they would only approve it as an elective, it felt like a kick in the gut. It was more people validating that we are not valued.”

Approving the African American and Latino studies course as a US History requirement would validate that the experience of marginalized peoples does not sit at the margins of US History. The course is highly aligned with the FPS Vision of the Graduate, as well as overarching US history events and themes. Students will walk out the door as more knowledgeable US citizens, especially in today’s globalized world. Offering the course as an elective would pose a barrier to students who still have to fulfill the US history credit and the civics credit, and likely do not have extra time and space for an additional full-year history course in their schedules. It’s also important to clarify that while Fairfield Public Schools is mandated to offer this course, students are not mandated to enroll in it, and every incoming junior would have several options to fulfill the history credit.

As senior Andrew McKinnis, leader of Youth for Equity at Ludlowe, shared in his public comment at the November 30 meeting, the course will continue to evolve. “As the course is taught next year, teachers will see how it can be improved for future years…Please do not let perfect be the enemy of the good,” McKinnis stated. The committee will continue to refine implementation, incorporating insights from the 50 Connecticut schools that piloted the course this academic year as well as continuing to engage the stakeholders–history teachers, house principals, students, and FPS administrators – already grounded in this work. We will reach for ideals, likely fall short of them, and continuously adapt our strategies in the same way that history is made. The Board of Education must not miss this opportunity to make history and serve as a model to other districts in Connecticut on how this course can be implemented with multiple stakeholders–and perspectives–in mind.

At the October and November presentations of the course, the BOE members asked deep questions, vital questions; the committee has done its due scholarship and diligence to address their concerns about rigor and course content. Now, as a community, we are asking the deciding question: does a course that intersects major themes of American history and cover 150 of the same historical events from new angles qualify as American history?

As a senior who took AP US History last year, I present my thesis, my evidence, my reflection over the compelling claims and counterclaims. Now it is time for the Board of Education to make a decision, especially cognizant of the perspective of students whose ancestors contributed greatly to the American story but have seldom had the story told from their vantage point of American identity and freedom.

Harper is the current Editor in Chief of Prospect. Harper served as the Opinions Editor of the paper during the 2019-2020 school year. This is her fourth...