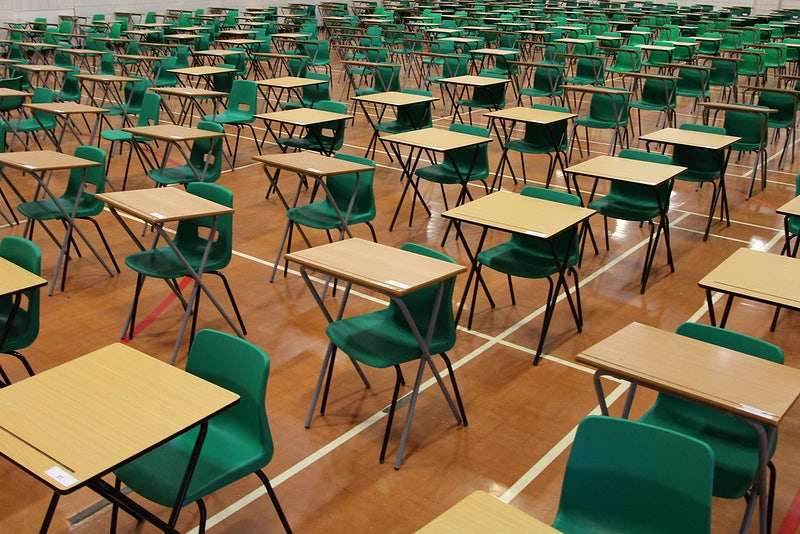

“And you think like, oh my God, I’m in this room where these major decisions are going to be made.”

On February 28th, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in an important gun law case that will determine the legality of some modifications to semi-automatic weapons—with two Falcons, former and current, being present in the courtroom.

Through a former student who interned at the Supreme Court last fall, Mrs. Bourque was able to travel down to Washington, D.C. for the day, where the two of them were able to go to the Court and hear oral arguments. Mrs. Bourque, an avid watcher of the Supreme Court, teaches history and civics at Ludlowe.

“It was really very, very cool,” she said. “We could see the front facade of the building, but we went in like the super secret side entrance. So I felt cool right off the bat. But even just walking the halls and there’s this big statue of John Marshall, who you know, Marbury v. Madison, McCulloch [v. Maryland]—it’s just there.”

The day’s case, Garland v. Cargill, stemmed from a dispute over the legality of bump stocks, which are devices that can be used to increase the rate of fire of a semi-automatic gun, allowing it to shoot at a rate close to that of a fully automatic weapon, such as a machine gun. A bump stock allows the main body of the gun to slide back and forth, with the recoil energy that is felt by the shooter causing the gun to bounce forward, with the trigger repeatedly bumping against the finger of the shooter causing the gun to fire rapidly.

With a bump stock equipped, one only needs to hold posture with the trigger finger in place and pressure exerted on the barrel and pistol grip, to allow the gun to keep firing after the first shot.

After the 2017 Las Vegas shooting, in which the gunman used rifles outfitted with bump stocks to increase the rate of fire and commit the deadliest mass shooting in American history, there were calls for the regulation or banning of these devices. In December 2018, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) issued a regulation classifying bump stocks as machine guns, banning them under a 1986 amendment to a 1934 federal law which makes civilian possession of machine guns largely illegal.

Michael Cargill, a resident of Texas, sued the federal government in 2019 after having to surrender his bump stocks, seeking to have the ATF rule overturned. A district court in Texas sided with the government, but the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit agreed with Cargill that bump stocks do not count as machine guns. The government then appealed the case to the Supreme Court, where Mrs. Bourque was present for oral argument.

Under the 1934 National Firearms Act, the statute at issue in the case, a machine gun is classified as “any weapon which shoots, is designed to shoot, or can be readily restored to shoot, automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.”

In very technical oral arguments, much of the disagreement in the case came down to the interpretation of what these words mean.

In the government’s view, a shooter applying forward pressure on the gun to begin firing—the human action—is the single function of the trigger, meaning that a bump stock-equipped gun fires multiple shots with one function, as a person only has to maintain that position for it to keep firing.

However, in the view of Cargill’s lawyers, a single function of the trigger is only when the mechanical trigger inside the gun causes one shot to occur—meaning that because the trigger has to mechanically reset and must bump into the shooter’s finger each time, a bump stock only fires one shot per function of the trigger.

A decision by the Supreme Court for the government would uphold the ATF ban on bump stocks, whereas a decision in favor of Cargill would make bump stocks legal again, further relaxing federal gun policy. But though this case will be impactful for gun policy, it was a statutory case, not a constitutional one—meaning it didn’t concern the Second Amendment.

“It was interesting in the sense that when you think guns, you think of the Second Amendment, and it wasn’t a Second Amendment case,” Mrs. Bourque continued. “At one point [Justice Brett] Kavanaugh brought up the Second Amendment and the other conservative justices particularly did not seem happy with that line of questioning.”

This case, she said, was really about how much power the bureaucracy has to interpret what the law means and what the legislative intent was. “The government was arguing that they had every right to ban bump stocks, that the law from 1934 says machine guns are illegal, and this piece put on the gun makes it a machine gun. So therefore it’s illegal,” she noted. “On Cargill’s side, they say they don’t know what the legislative intent was. And it’s an overreach by the bureaucracy to say that a bump stock is a machine gun.”

However, Mrs. Bourque also sees the attack on bureaucratic power as broader, noting that the principle of Chevron deference, where the courts have allowed more leeway to bureaucratic agencies filled with experts to do their job, has been under attack this term of the Court—and that this was just another piece of that attack. “My guess is Chevron [deference] will go down,” she said, “And it will limit the regulatory ability of the bureaucracy. I hate to say this, because the justices are not supposed to be political, but they’re political. I think that one of the aims of this whole term is to weaken the regulatory power of the bureaucracy,” she noted.

Mrs. Bourque said she thought the case was purposefully argued as a regulatory case instead of a constitutional case because it would have gotten more attention as a Second Amendment case. But it would have also been hard to argue, she said: “You know, that the whole reason they banned bump stocks was because of the most horrible mass shooting in United States history, where 60 people died in Vegas, and the guy used bump stocks. It’s kind of hard to argue that he should have this kind of gun.”

“I don’t think they would have won the Second Amendment case,” she continued. “Because I think everybody would have said it was a machine gun, which in 1934, was made illegal because of Al Capone and the gangsters at the time.”

However, Mrs. Bourque still isn’t sure how the Court will rule. “Going in, I was sure it was gonna be 6-3 [against the government],” she said. “But I’m going to go 5-4. I think Alito is going to vote in favor of the government,” she stated.

But she wonders how much oral arguments actually shape the opinions of the justices. “I asked this of Chris, my former student, [did he] know how much they come into these and they already have their mind made up? It seemed like during the first half when they were questioning the deputy solicitor general, the minds were made up on both sides,” she said.

“But then the questioning changed when Cargill’s lawyers came out. And I asked Chris this and he couldn’t really answer. I think for me, it will be interesting to see how they rule,” she noted.

“Because if it’s 5-4, then oral arguments do make a difference. If it’s 6-3, they don’t.”