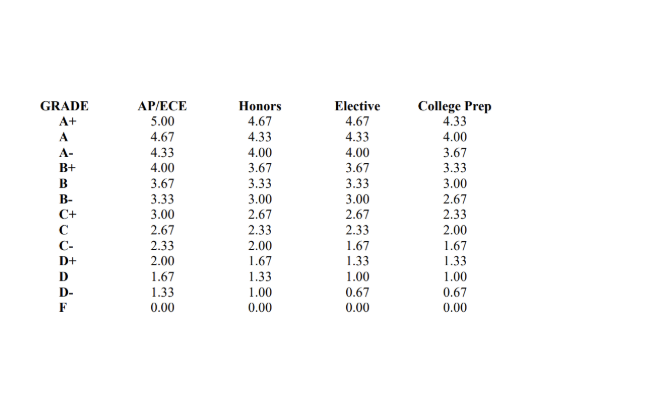

As per the FLHS program of studies, different level classes—that is Advanced Placement (AP), Early College Experience (ECE), Honors, and College Preparatory—have different numerical values assigned to them per letter grade. For example, an A+ in an AP class is weighted significantly “heavier” on one’s Grade Point Average (GPA) than an A+ in a College Prep class.

Students who take more AP and Honors classes generally have higher GPAs; the math works out. Take two students, one taking the AP class and the other taking College Prep class. If the AP student has an A- in the class, the numerical value it will hold is a 4.33. If the same grade is achieved in the College Prep class, it will hold a 3.67 value. That 4.33 of an A- is equivalent to an A+ in the College Prep class.

While this system rewards those who take AP classes and perform well in them (allowing for extremely high GPAs) it puts students in lower level classes at a disadvantage.

Students have noticed this: As the college process becomes more and more competitive, the pressure to take APs has heightened.

But, it is not just the college process; it is a system that propagates competition and a need for GPA boosts, causing some students to feel discouraged.

A Fairfield Ludlowe senior shares that she tries “hard in [her] classes and has decent grades.” Yet, she wonders “why doesn’t my GPA compare to others?” The boost that higher level classes have can make students unable to take AP classes feel left behind. Commenting on the rise of her GPA, the student adds that she “thought [she] just couldn’t get [her] GPA high for whatever reason. But now it is [getting higher] because [she] is just taking two harder courses.”

Additionally, there is a lot of animosity around how GPA is scaled. Students feel as if they don’t really know what is going on. Junior Nishka Desai comments that “our GPA is very much inflated and also very confusing, I feel like it’s almost kinda hidden on how they are calculating it cause the only place you can really see how it is calculated is in the program of studies.”

The argument for weighting is that students who take higher difficulty classes should have different weighting, since the levels of the courses are, in theory, more rigorous. Ms. Vanessa Montorsi, Director of Pupil Services and Counseling, explains that the system is a “way of giving back and making people, like, ‘Hey, challenge yourself, but don’t feel bad about it.’” She continues, saying that “we want to favor students to challenge themselves and not feel like, ‘Well, I want to challenge myself, but I don’t want my GPA to get dinged in a way.’”

Ms. Montorsi also emphasizes that the weighted GPAs are only “valid” inside Ludlowe. Since the scale each school weighs is different, most colleges “will re-weight” GPAs. For example, depending on the college, “they’ll take Health and Phys-Ed out or maybe potential other elective areas classes. They do it because every school is on a different, not always on a 4.0 scale. There’s a school out in California that’s on a 20-point scale. So, it’s so vastly different. It forces the colleges to take apples and oranges and then put everybody on the same playing field,” she clarifies.

The counseling department has not seen the system have a quantitative effect on students. “If you’re looking at a straight GPA, they’re not going to attain a higher level GPA,” Ms. Montorsi explains, referring to a College Prep student. Despite this, she questions if that’s “necessarily a drawback.” “Maybe it is for colleges that are truly looking at a weighted GPA scale. I’ve never seen it impact any of our students,” she continues.

The GPA weighting system, while benefiting some, can have negative effects on those who cannot take higher level classes. However, GPAs can be looked at on an unweighted scale, leveling out the playing field.

Some students feel there could be reform as to how GPAs are weighted. Senior Jack Emra shares his potential solution. “The best way to solve the GPA inflation problem is looking at the classes and deciding whether certain classes should really be given honors weighting, especially in electives. I would also want to see more of a focus on choosing classes that align with people’s interests, not just what is easier to get an A in, which I think could happen by finding more classes that people can take that can expand or create an interest in business, politics, math, history, science, etc,” Emra comments.

On less “academic” classes, Ms. Montorsi adds that the administration is “looking to get a Fashion Design class and an Art or Photography class that is an ECE class. We’re starting to look at other avenues as opposed to the traditional core academics.”

Ms. Montorsi emphasizes the importance of taking classes because of content and interest, not the possibility of a GPA boost. “If you’re just taking classes because you think you have to take them, that just would be miserable. And I think there’s so much stress in today’s society, especially with students. Don’t do it. I like to tell students to take classes that you’re potentially interested in and maybe that’s a pathway you want to go. But for the straight, just like GPA, I don’t necessarily agree with it,” she added.

At its core, the GPA weighting system allows for students to take academic risks and be rewarded. The administration’s emphasis on course fit, rather than societal pressure, should be echoed louder. For now, it remains as a game only a select few have an advantage in, a game of weighted dice.

As more and more students chase the GPA boost, even when they can not handle the class workload, classes become slowed down. Each level of rigor should, in theory, be rigorous to the student that “belongs” on that level. That is, if one is at the College Prep level, they must be challenged by that class.

Instead, classes are becoming easier and students don’t feel challenged. Students, not being challenged by the classes they are supposed to be challenged by, move to higher level classes and later, struggle. This just causes a cycle of failure, and classes that are supposed to be difficult become easier to accommodate for students who are not prepared.

The question then rises: why should students who take harder classes get rewarded? If a student is taking an AP class, it should be to challenge themselves because they have room to be challenged. The knowledge and advancement of skills is the reward—as well as the reward through the college process.

Ludlowe’s GPA system is easy to exploit in order to get a high GPA. More than a security net, it serves only those who know how to exploit it. This increases stigma around taking “lower” level classes and causes students who are not ready to take harder classes.

College Prep classes should only be easy to those who belong in Honors or AP classes. They should actively challenge students and prepare them for higher education post graduation. Students who feel challenged by these classes are right where they are supposed to be. But it does not feel like it. Even if these students achieve all A’s, they would never reach the GPA of an AP student that has A-’s.

There is no need to reward AP or Honors students, the college process will. All this says to students in College Prep classes is that they will never be good enough. Without this weighted system, students would feel more free to take the classes that challenge them and fit best for their level, not what reflects best on their GPA.

![[Charlie Kirk] by [Gage Skidmore] is licensed under [CC BY-SA 2.0].](https://flhsprospect.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/charlie-kirk-article-1200x800.jpg)