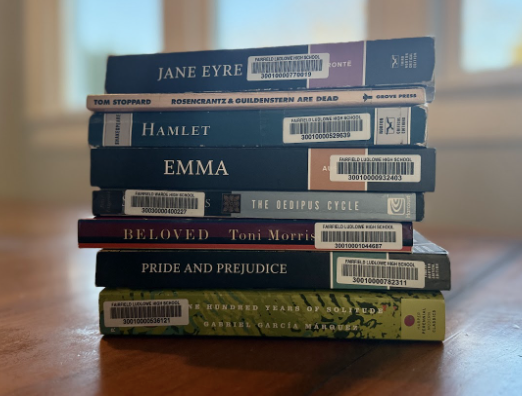

As more Artificial Intelligence (AI) assistants, like ChatGPT, and reading guides and summaries, like SparkNotes, become available, it has become increasingly easy for students at Ludlowe to not read the assigned book in English class. In all levels of English classes, teachers are seeing more and more students relying on outside sources instead of reading the assigned materials. If these resources are available, what is the value of actually reading the book assigned in class? To find out, I interviewed Ms. Ingram, an AP Literature teacher and English department liaison, who sees this as a troubling trend.

I began our conversation by asking a basic question: why should we read the book in English class? For Ms. Ingram, the answer was simple, “why wouldn’t you want to read the book?” For her, one of the most important reasons was for a person’s “authentic intellectual development,” to not simply be reliant on other people’s ideas. While she recognized that it is getting easier to get away with not doing the work, ultimately, you are just “cheating yourself out of an education” and “never truly having to think and develop an opinion of your own.”

For many students, these consequences may sound like an extreme characterization of just not reading a book. But for Ms. Ingram, it is about far more than not doing your homework. To her, choosing not to “develop your own understanding of your language” will just lead to ignorance. Rhetorically, she asked, “do you want to be an ignoramus?”

Literature, as she put it, is representative of the “human experience” and it teaches us “what it means to be human, what it means to be moral.” But all of this is lost when the book is never read.

As for the effectiveness of just using SparkNotes and AI, Ms. Ingram says “it is easy” to tell when a student doesn’t read the book or write their own paper. Now that teachers are giving more timed essays in class, she can see the difference between what they are able to produce independently in class and what they can produce when they are being influenced by an outside source.

This trend is larger than students not doing their class work. “We live in a culture where integrity and morality are not valued as much as expediency and getting away with things.” This, she added, was likely the fault of older generations. But she does not let this affect how she works. As she told me, she “reads everything that kids write for [her],” hoping to serve as a model for others.

To conclude our conversation, I asked her what she gets out of teaching these books. Some of her “best moments,” she said, are hearing how students “bring all their own experiences and how they see the world” to discussing these novels. That, she believes, “makes the experience rich for me.”

The optimism that Ms. Ingram displayed in our interview truly summed up why I believe we all should listen to her advice. Even while it may be easy to get an A without reading the book or doing the work for yourself, there is value in reading far beyond just a grade. The books I have read this year in AP Lit with Ms. Ingram have raised philosophical and moral questions and have also made me think about what it really means to be human.

Literature truly is about educating one’s mind and one’s soul. If you don’t believe me, read the books in your class and find out.

![[Charlie Kirk] by [Gage Skidmore] is licensed under [CC BY-SA 2.0].](https://flhsprospect.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/charlie-kirk-article-1200x800.jpg)