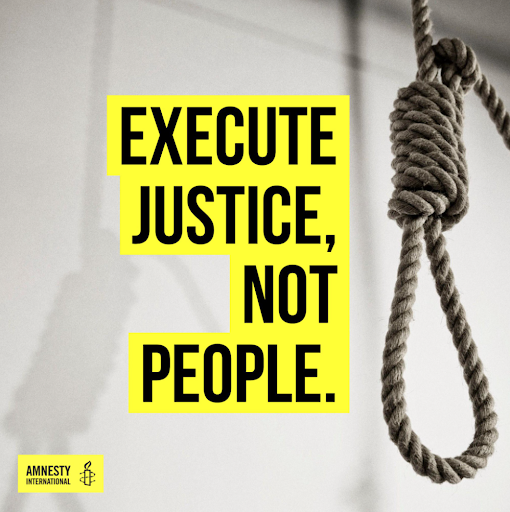

The Injustice in Justice: Why the US Should Abolish the Death Penalty

On January 16, Dustin John Higgs was the 13th person executed by the US government since the Trump administration resumed the death penalty in July 2020.

As the Trump administration has carried out an unprecedented 13 executions since resuming the death penalty in July 2020, the ethics of capital punishment have again been thrust into the national spotlight. As it exists in the United States, the death penalty does not maintain justice but instead perpetuates discrimination against the marginalized, arbitrary punishment, and harm against the innocent.

Prior to 2020, there were no federal executions since 2003, and only 3 federal executions since the federal death penalty was reinstated in 1988, according to CNN. Six inmates, Orlando Hall, Brandon Bernard, Alfred Bourgeois, Lisa Montgomery, Cory Johnson, and Dustin Higgs, have been put to death following the election on November 3, 2020. The Guardian emphasizes that the last time a “lame-duck” president went through with an execution was in 1889.

One of the main arguments for the death penalty centers on retribution: In theory, guilty people who commit murder and other heinous crimes should deserve to be punished. However, the death penalty is only applied to a random sampling of convicted murderers in the US; the difference between the death penalty and life imprisonment without parole rests on the arbitrary sentencing of judges. These decisions are often influenced by the victim’s race, level of education, or state of residence. Reports show that 41% of the defendants executed this year were Hispanic or people of color, but 76% of the executions were for the death of white victims. All but one execution during the transition period involved Black male offenders. If a punishment is not being applied consistently, and the psychological agony of waiting decades on death row delivers a more severe punishment than the initial crime, what is theoretically justice becomes, in practice, injustice.

The execution of Brandon Bernard, an African American man, in December 2020 illustrates the issue of racial discrimination in the criminal justice system. Bernard was one of five gang members charged in connection to the killing of the Bagley’s, two youth ministers, in 1999. He was convicted in Texas, along with Christopher Vialva, the gunman, who was executed in September. The other gang members were given lesser sentences, which raises the question of why Bernard received such a serious sentence as he did not pull the trigger.

The full evidence surrounding the crime and Bernard’s involvement in the gang was not presented at his trial in 2000; instead, it was withheld by prosecutors that sought to label him as a future danger to society. CNN writes, “Five of the sentencing jurors came forward saying that if they had been aware of the undisclosed information, they would not have agreed to sentence Bernard to death.” Bernard’s attorney, Robert Owen, wished to have a hearing with the new evidence presented; however, even with pleas from major public figures, the US Supreme Court denied a stay of execution, and President Trump refused to reconsider or postpone the execution.

It is no coincidence that the Trump administration has carried out more executions than any other president in history, even during a pandemic. It is also no coincidence that all of the state executions in 2020 were in Southern states—Missouri, Texas, Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia—according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The death penalty projects from the legacy of slavery, Black codes, and lynching. In the 28 states where the death penalty still stands, it arbitrarily determines which offenders are punished to the highest degree and which lives are valued.

The death penalty is also deemed to be a deterrent for crime, but this too is unproven. Statistics suggest that it actually does the opposite. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, “The average murder rates for death penalty states was 5.4 [murders per 100,000 people], while the average murder rate of states without the death penalty was 3.9 [murders per 100,000 people].” It is impossible to establish a direct correlation between a person’s decision to commit a crime and the existence of the death penalty, because many different variables are involved. However, if the death penalty has not been shown to decrease violence, and it more likely promotes an environment of brutality, can the loss of human life ever be justified?

In a criminal justice system that continues to convict the innocent, the death penalty has been applied to innocent lives. According to the Equal Justice Institute, for every nine people executed, one person on death row has been exonerated. Police cover-ups, invalid forensic methods, faulty eyewitness testimony, coerced confessions, and lack of investigation have all led to wrongful sentencing. How can the death penalty be justified on the basis of retribution if people are innocent of the crime they were accused of committing? Human life has inherent worth. The loss of innocent life in murder, and an innocent life being taken by the state are both unconscionable.

Debate on the Constitutionality of the death penalty has centered on whether it qualifies as “cruel and unusual punishment” under Article 8 of the US Constitution. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, “Every prisoner executed in 2020 had one or more significant mental or emotional impairments (mental illness, intellectual disability, brain damage, or chronic trauma), or was under the age of 21 at the time of the crime for which he was executed.” Christopher Vialva was 19 and Brandon Bernard was only 18 at the time of their crime; the human brain does not fully develop until the age of 25. It is cruel and unusual to execute the most vulnerable, those who did not have full capacity for judgment when they committed an act of violence.

Bernard expressed remorse for his past actions before his death. “I’m sorry … I wish I could take it all back, but I can’t,” Bernard said to the Bagley family during his three-minute last words. “That’s the only words that I can say that completely capture how I feel now and how I felt that day.”

The death penalty is complicated, crossing into questions of racial discrimination, intellectual disability, justice, and ethics. One thing is clear: the speed at which 13 federal executions have been conducted in the past six months displays a fundamental disregard for human life. Our nation should feel remorse. Substituting the death penalty for life imprisonment without parole in all states and at the federal level would not right the wrongs of heinous crimes or solve the underlying issues in the criminal justice system. But it would end a method of punishment that is fraught with injustice and discrimination. Capital punishment in the United States is not just retribution. It arbitrarily, and irrevocably, determines which lives matter.

Bernard’s attorney, Robert Owens, stated, “Brandon’s execution is a stain on America’s criminal justice system. But I pray that even in his death, Brandon will advance his commitment to helping others by moving us closer to a time when this country does not pointlessly and maliciously kill young Black men who pose no threat to anyone.”

Harper is the current Editor in Chief of Prospect. Harper served as the Opinions Editor of the paper during the 2019-2020 school year. This is her fourth...

Charlotte is the Spotlight Column Editor for Prospect. In 2020-2021, Charlotte was the Consumer Reviews Editor.